Austin Bush has been hanging out with me in Melbourne over the last week and we’ve been doing the sort of thing that food bloggers do when they run into each other: drink every single pale ale made in Australia and New Zealand; eat several times a day with no regard for socially accepted “meal times”; and cook food that takes regional authenticity to ludicrous lengths which he has amply documented on his Thai food blog.

Both Austin and I are huge fans of Northern Thai food, the cuisine that skirts the Burmese border in Thailand’s northern provinces. He’s been spending plenty of time up there and myself, not nearly enough. Austin came up with a menu.

Here’s my take on it.

Sai Ua

I’d been keen to make David Thompson’s recipe for sai ua in his book Thai Food for quite some time. It’s a greasy pork sausage from Chiang Mai that is packed full of chilli, lemongrass, coriander, shredded lime leaves and hog fat. You spot it throughout Northern Thailand as a street food, chopped into bite-size chunks and served in a plastic bag. The chilli-reddened grease from it coats the inside of the bag and as a consequence, your hand.

When I came across the handful of sausage recipes in Thai Food, it did make me wonder, how many of these recipes have ever been cooked by the owners of Thompson’s tome? Chiang Mai sausage making requires an interlocking interest in regional Thai cuisine and charcuterie. In my experience, these fascinations tend to be mutually exclusive.

I’m not going to repeat the recipe here. Do David Thompson a favour and buy his book. Recipe is on page 518. My liner notes for the recipe:

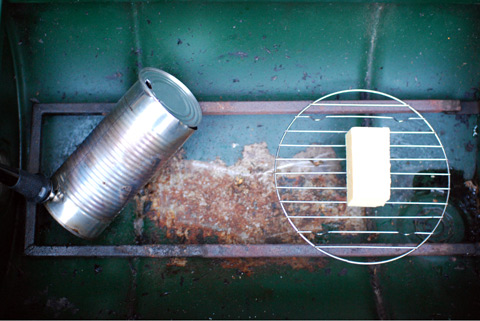

- There is no need to smoke the sausage over dessicated coconut. Just grill it over an open fire. I get the feeling that Thompson added this step because it works in a commercial kitchen. If you’re cooking commercially, you can smoke the sausage in advance then finish the sausage on a flat grill because it is much quicker than the leisurely route of slow-cooking it over coals.

- More chilli. The recipe suggests 6-10 dried chillies and we used about 20. If you feel unsure about this, grind up the sausage mix with only half the chilli then fry up a test patty. We still didn’t get the color quite right – it needed to be redder. The next batch that I try will use a mix of powdered chilli and dried chillies. Otherwise the mix of herbs is spot on.

- If you’re using a commercial sausage maker, use the coarsest grind available and aim for a fat content of around 35-40%. They’re fattier than your average sausage and don’t need to bind as firmly as a western sausage. The herb mix can run straight through the meat grinder instead being pounded into a paste as Thompson suggests. The result is much closer to Austin and my recollection of Northern sausages, which have very coarse chunks of lemongrass and fine shards of lime leaf still intact.

Kaeng Hang Ley

Austin brought with him a collection of spices from Mae Hong Song, including the freshest turmeric powder I have ever smelled and the local Mae Hong Son “masala” powder, so we hit up Footscray for fresh ingredients. If you’re keen on making this particular curry, Austin has the hang ley recipe. For Thai ingredients in Melbourne, visit Nathan Thai Grocers at 9 Paisley St in Footscray. They’re amazingly well stocked with Thai goods and have a pre-prepared Hang Ley paste. At Nathan, we could find a Thai-brand sweet sticky soy and shrimp pastes just to take the dish to an extreme of regional correctness. As a coincidence, I already had Thai tamarind pulp (which is really no different from any other tamarind).

Pork belly is official local meat of Footscray. It can be found at every single butcher in the suburb, apart from the two lonely Halal meateries. I buy mine in Footscray Market because there are enough suppliers there that you can always pick out the right piece.

Saa

This recipe calls for young pea shoots and leaves, we had to settle for some slighty older and more bitter ones from Little Saigon Supermarket in Footscray. Multiple vendors had deep fried pork skin used to top this salad, but the Northern Thai-style of pork crackling which is cut into thin strips was nowhere to be seen.

Key Sources

Nathan Thai Video and Grocery, 9 Paisley St, Footscray. They’re friendly guys and even have a blog, documenting incoming Thai videos.

Little Saigon Market, 63 Nicholson Street, Footscray. Best for vegetables from across Asia. Also a good spot to pick up hard to find dried fish.

Footscray Market, 81 Hopkins St, Footscray. I only visit here for meats, mostly fish and pork.